Show is crammed with hilarious one-liners and joyful nostalgia

Kate O'Neill

For the Lansing State Journal

January 20, 2011

Just last month, Stormfield Theatre brought the irreverent Mark Twain (via Richard Henzel) to its intimate stage in the Frandor Shopping Center.

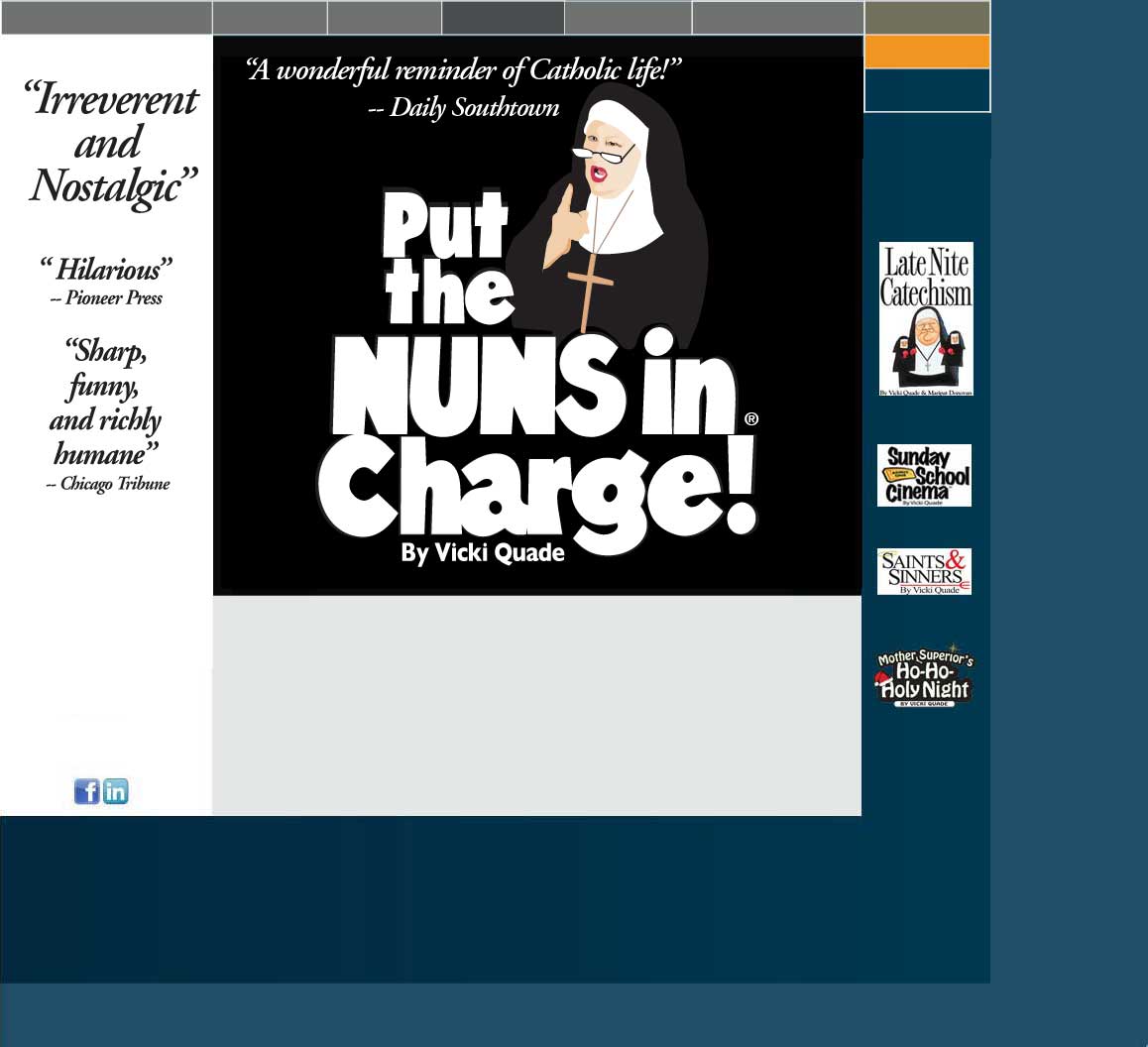

Now Stormfield has another equally audacious visitor, Mother Superior (Breeda Kelly Miller), who counsels us to "Put the Nuns in Charge!"

This one-woman show is one of a series of plays about nuns (including "Late Nite Catechism") which Vicki Quade has written over the past 18 years.

Quade has injected many opportunities for improvisation by the actress playing Mother Superior, along with many opportunities for audience participation.

The result is more in the nature of a stand-up comedy routine, and Miller proves she has a fine command of this medium.

The audience for the show arrives at the theater to find a stage equipped with all the trappings of a parochial school classroom - religious pictures and a photo of the present Pope on the walls, a teacher's desk, and a blackboard inscribed with the Seven Deadly Sins.

With the arrival of Mother Superior to teach her Good Behavior Class, it becomes clear that she considers the audience her pupils, and they will be expected to listen reverently to her every word.

Early on, she asks how many in the audience are Catholic and how many went to parochial schools.

On the night I attended, about a third of the audience raised their hands to both questions. For them, this show was crammed with both hilarious one-liners and joyful nostalgia.

For almost 90 minutes (minus a brief intermission), she had me really convinced that she was Mother Superior, as she brandished her ruler, reminding those she called upon to give their full names - not their nicknames - and always respond, "Yes Sister."

With Miller on stage, the nuns are truly in charge at Stormfield Theatre.

Second to nun

Breeda Kelly Miller is a class act in wacky comedy

by Mary C. Cusack

Lansing City Pulse

January 19, 2011

Put the Nuns in Charge! is presented as an interactive, adult education lesson in morality, with the audience members playing the class. Under the stern gaze of a portrait of Pope Benedict, as well as the equally stern, over–the-glasses gaze of Mother Superior (Breeda Kelly Miller), the audience learns about saints and sinners, speeding nuns, and the difference between indulgences and over-indulgence.

Similar in tone to the musical “Altar Boyz,” the play pokes gentle, affectionate fun at the sometimes puzzling beliefs and practices of the Catholic Church. Even though she brandishes the stereotypical knuckle-wrapping ruler, Miller’s Mother Superior is charming and slightly goofy, yet sincerely dedicated to spreading the Good Word.

Michelle Raymond’s set is a perfect reproduction of a parochial elementary school classroom, right down to the handwriting letter chart and poster of the U.S. presidents. Many of these props are functional to the script, such as the apple-shaped container on the Mother Superior’s desk that holds her stash of glow-in-the-dark rosaries. The rosaries, along with her pocketful of trading cards of the saints and other related goodies, serve as prizes for those audiences members game enough to play along with the play.

Miller is adept at reacting to her environment and utilizing the set and props to increase audience participation. On opening night she nailed a smarty-pants in the audience within the first few minutes, bringing him onstage and making him put his nose in a circle she drew on the chalkboard. The simple act of drawing the circle on the board and pointing to it elicited chuckles of familiarity from the audience.

There are patterns built into an interactive show such as this. Picking on one miscreant early in the play allows Miller to build continuity with her audience as participating class members. It also affords her the opportunity to show off the Catholic virtues of redemption and forgiveness, as the rotten apple regained the Mother’s favor in the second act.

The list of sins on the board served as the foundation for the script, upon which Miller could pile contemporary stories and examples of sin. On opening night, for instance, Miller’s material included text messaging, movie theater etiquette, celebrity nuns and Bill Clinton.

“Put the Nuns in Charge” is accessible to and fun for audiences of any or no religious background. It is a silly, crowd pleasing guilty pleasure, which shouldn’t come as a surprise: After all, Catholics and guilt go together like bread and wine.